Hello my friend in desktop mode.

Hello my friend in desktop mode.

Hello again my friend in desktop mode.

Hello again friend in mobile mode.

Bill Condie

HOW RESEARCHERS CHANGED AUSTRALIA’S RIGHTS OF APPEAL LAWS FOREVER

—

Their tireless crusade against miscarriages of justice turned more than 100 years of established law on its head, giving hope to those jailed for crimes they didn’t commit.

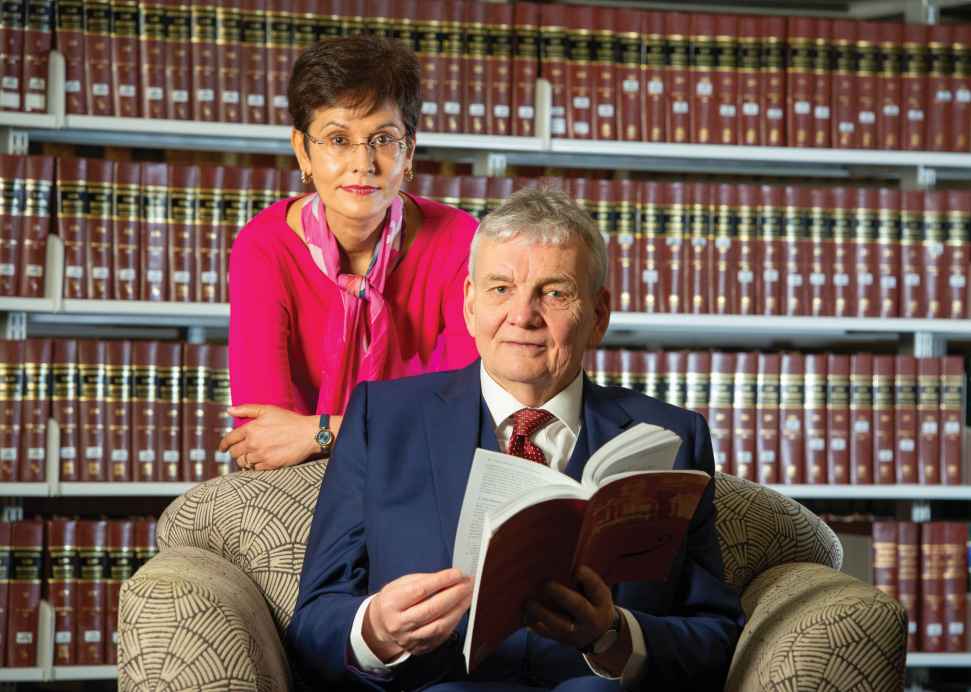

Associate Professor Bibi Sangha and Dr Robert Moles – quiet revolutionaries at Flinders University – made history in 2013, with the establishment of a new statutory right of appeal for criminal cases.

This new right has already resulted in three convictions being overturned, but it was a movement that the legal establishment in Australia fought every step of the way.

“Miscarriages of justice are going to upset a lot of powerful people,” says Dr Moles. “The trials are costly and long, and then someone comes along and suggests that the conviction may be wrongful. Well, there are a lot of people who don’t want to hear that.”

The case that started it all was that of Henry Keogh, a banker jailed erroneously for 26 years in 1994 for the murder of his fiancée. Keogh spent 21 years behind bars before walking free in 2015, receiving $2.57 million in compensation from the government.

New evidence had saved Keogh, but that evidence would not have been heard without Associate Professor Sangha’s and Dr Moles’ long fight to allow old cases to be re-opened.

Less than a decade ago, appeals to re-open old cases were almost never allowed, under a long-established legal principle in Australia.

Bibi graduated with BA (Hons) in Law from Middlesex University in the UK. She went on to complete her LL.M at the London School of Economics. She was called to the Bar at Lincoln's Inn in London. She has also been admitted to practice as a Barrister and Solicitor in Malaysia, the Australian Capital Territory and South Australia. She appeared before the Privy Council in the last case on appeal from Malaysia. Prior to joining Flinders Law School, she was a lecturer in law at the Australian National University.

Dr Robert Moles is a legal academic and researcher well known for his expertise and writings on legal theory and miscarriages of justice. He has published books mainly in the areas of miscarriages of justice.

“Clearly, being sent to prison for something you haven’t done is a nightmare to the individual, and utterly abhorrent in a free society.”

“Whenever you took a case back to court that had already gone to its normal appeal, the court would not easily re-open it,” says Associate Professor Sangha. “And it did not matter how compelling the fresh evidence was.”

This meant that there were cases slipping through the cracks.

When the researchers took the Keogh case to the High Court in 2007, the judges acknowledged the potential for a miscarriage of justice, and noted that the law could be changed.

Although, at the time, their hands were tied by the existing law.

Associate Professor Sangha and Dr Moles had began their work in 2002, collaborating with experts such as forensic scientists and pathologists to identify cases that had relied on potentially incorrect ‘expert’ evidence, leading to wrongful convictions.

“Clearly, being sent to prison for something you haven’t done is a nightmare to the individual, and utterly abhorrent in a free society,” says Dr Moles.

He and Associate Professor Sangha were met with deep reluctance to change the status quo.

“Strangely, the principle of double jeopardy – the longstanding legal principle that no one can be charged twice for the same crime – became our ally,” Dr Moles explains.

The principle of double jeopardy was being re-examined in Australia at the time, in the light of several cases where evidence that might have resulted in a conviction was not heard in the original trial.

The law was changed so that, in some cases, where there was fresh, compelling evidence, a retrial could be ordered.

“So, the argument we made was that, if the prosecution can have a second go, why can’t the convicted person?” says Dr Moles.

The careful language and demanding tests used in cases of double jeopardy provided a path that could overcome the arguments against allowing a free-for-all in appeals.

From 2007, with help from Flinders University staff, the researchers ran an extensive media campaign to explain the problem to the Australian public, and began further research into miscarriages of justice, engaging with other jurisdictions with similar experiences.

In November 2012, the South Australian Government presented a Bill, which was adopted unanimously by the parliament and came into effect in May 2013, allowing for appeals where there was “fresh and compelling” evidence that might give rise to a finding that there had been a “substantial miscarriage of justice”.

Similar legislation has since been enacted in Tasmania, and is currently before the parliament in Western Australia.

As former Justice of the High Court Michael Kirby noted: “Sometimes in Australia, principle triumphs over complacency and mere pragmatism”.

![]()

Sturt Rd, Bedford Park

South Australia 5042

South Australia | Northern Territory

Global | Online

CRICOS Provider: 00114A TEQSA Provider ID: PRV12097 TEQSA category: Australian University